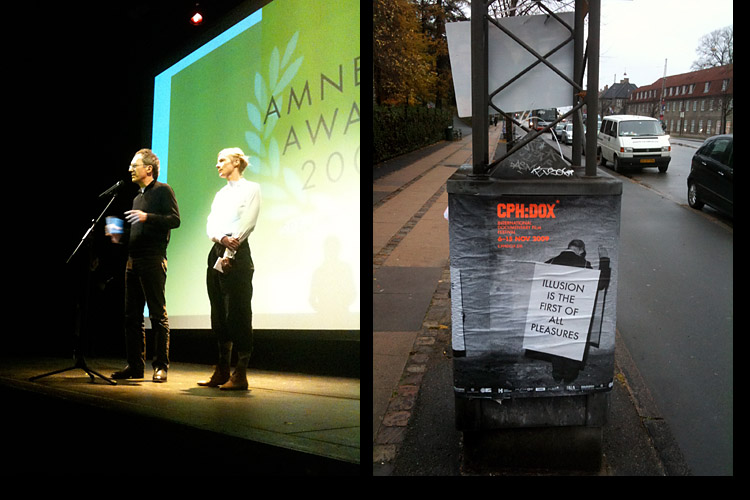

James Der Derian and Maja Borg announce the winner of the CPH:DOX Amnesty Award

By James Der Derian

Five grey and rainy days in Copenhagen, each one fading early into a Nordic nightfall: great weather for a film festival, not so great for getting rid of a lingering jetlag. Just about every bar and restaurant beckons with lit candles from windows, table-tops and counters. Welcoming, but as I found out during an earlier visit to Copenhagen, potentially dangerous. After giving a talk on the work of Paul Virilio, I went with a group from the conference to a nearby watering hole, where I kept getting backed up against the bar by one eager student after another. After several minutes of this I smelled something nasty and realized my favorite blazer – a silk job, the product of watching too much Miami Vice back then – was ablaze, thanks to the one of the ubiquitous candles. The barmen nonchalantly threw a glass of water on my smoldering jacket.

I learned early on that Danes don’t make much of a fuss about life’s little calamities or big accomplishments, which kind of set the tone of the CPH:DOX festival, and distinguished it from Florence. Everybody seemed pretty content, nobody overly demonstrative about films, food or life in general. Probably the most exciting event happened when I nearly got kneecapped by a short guy on a short bike. With more bikes than cars on the road at any given time, you really need to be on your toes against two-wheeled threats, especially when ridden by small people (I think I lost the respect of my Danish host when I told her that a midget on a bike had nearly run me over).

My first stop was the Kunst Museum, always a great visual smorgasbord but now peppered with some spectacular and whimsical exhibitions for the upcoming Climate Change conference, including the didactic ‘Nature Strikes Back’, in which Foucault confronts Rachel Carson. But the art is really just an excuse to visit the airy restaurant that looks out over the royal park, where a plate of three varieties of herring and a glass of aquavit, can be had for 95 Kroner (the Danes are one of the last EU holdouts against the Euro, making for some confusion).

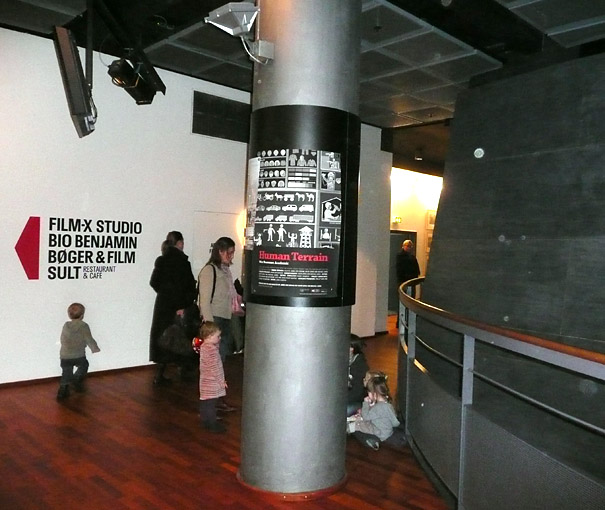

Fortified by works of art and water of life, I headed down to the Cinematak, where the CPH:DOX festival had set up its headquarters and we would be screening ‘Human Terrain’. The Odeon theater in Florence might have several centuries on it, but the Cinematak is just what one wants for a positive filmic experience: a bookstore, multiple cinemas, a very good restaurant and a long bar, all customer-friendly thanks to that permanently appealing face of modernity, Danish Design.

That evening we screened ‘Human Terrain’ as part of the Amnesty program (out of competition – still hoping for that North American world premiere). The intrepid Udris brothers, David and Michael, had braved IcelandAir the same morning and, rejuvenated by the hotel spa, joined us for a pre-screening dinner and a couple of Carlsberg drafts. The CPH:DOX organizers had laid on a special event with Copenhagen University, ably represented by Lene Hansen (Professor of Political Science and good friend) and Afghanistan expert Peter Dahl Thruelsen (Danish military, recently returned from Afghanistan, now a PhD student). The cinema was packed out, so after doing a brief intro I took a seat up high in the aisles, a fine perch to watch again for audience reactions. Like Florence, they looked pretty rapt; unlike Florence, there was no lag in the responses, more laughter at the right moments, and not a few displays of emotion at the end…

I think the Q&A was the best we’ve had, thanks to a good mix of academics, military, and hoi polloi. David handled all the questions that invoked big ideas (including one on ‘the dialectics of the film’), Michael on the politics of HT and pragmatics of filmmaking, while I tried to convey the hazards of walking the line between empathy for Michael and the need to do justice to all sides of the HT controversy. I also tried to explain why, after too many years of getting up close to the war machine, our next documentary was going to be on peace, love, and understanding (pace Costello and Lowe).

My duties really began the next day: jury duty for the Amnesty Award category of films that focus on the struggle for human rights. That meant spending a lot of time in the dark at the Husket Cinema with three other jurors, screening in private twelve films in competition. That’s four films a day over the course of three; by the end I’d say we were all pretty much ready to give up on humanity (or at least every intolerant religious, ethnic or political group claiming to act in the name of humanity) and join the next revolution (still-born or not). The first film, ‘Murder’, screened at 9 am in the morning, showing in graphic detail the consequences of Nicarauga’s draconian anti-abortion policies, with syringes, fetuses, and the high price of patriarchy on full display: not lite entertainment. There was some whimsy in the next film, ‘Erasing David’, which tracks one slightly nerdy filmmaker’s effort to evade Britain’s ubiquitous surveillance state. After that came José Padilha’s stunning black-and-white ‘Garapa’, a two-hour, fly-on-the-wall (and on the food, malnourished child, and mangy dog) account of daily life in the slums of Brazil’s mega-cities. Nobody had much of appetite for lunch that day.

After three days of this, our fellow jurists, Ryan Harrington and Helle Faber had to leave, so the ineffable Maja Borg and I were left holding the bag for the awards ceremony. We cobbled together some rough remarks at the hotel bar; but then I had to rush off for a beyond-the-call-of-duty, home-cooked Danish dinner prepared by Lene and attended by the extended Hansen-Kjaer-Mbamba families, so revisions were done by iPhone exchanges. We made it back to the Royal Danish Theater in time for a Jameson cocktail (a sponsor of the festival) before we took our seats. The tone of the awards was informal yet …honorific. Our category was one of the last; this is what we had to say:

The films in this year’s program for the Amnesty Award reveal the dark side of globalization, the forgotten victims of poverty, war, and injustice, and the struggles of individuals facing the loss of livelihood, freedom, and human dignity. The panorama of human suffering is extensive, reaching from Siberia and China to Mexico and Nicaragua, from Israel and Iran to Britain and the United States. The films are not abstract manifestos; they are human stories told in cinematic detail. Witnessing human rights takes considerable courage and many of these films do not make for easy viewing. It is difficult to pick out a winner when so there are so many wrongs to be righted, from the repressive antiabortion policies of Nicaragua conveyed in the film ‘Murder’ to the insidious and relentless effects of malnutrition in the slums surrounding the mega-cities of the Global South, so brilliantly depicted in ‘Garapa’. But two films stood out for their ability to expose injustice while both educating and entertaining the audience.

The jury would like to present a Special Mention to a film that manages to add a unusual and valuable perspective to a very sensitive and important issue, and at the same time succeeds to capture the audience with its humor and respectful warmth towards its characters; Yoav Shamir’s ‘Defamation’.

We would like to give this year’s Amnesty Award to a film that is an extraordinary example of the power of documentary to effect a real change. Both through using the camera as a direct tool for justice, and through managing to emotionally motivate the audience to take action by an amazingly well composed story and a unique access to its subject: ‘Presumed Guilty’, directed by Roberto Hernandez and Geoffrey Smith.

Then yet another after-party, with many of those memorable-at-the-time conversations that are rarely remembered the next day. Towards the end of the evening I began to feel like a stranger in a strange place and thought it time to head home to the dull(er) life of an academic – at least until the next festival (en shallah).